Size:

4.5 meters (15 feet) long and 200 kilograms (450 pounds).

Location:

Ischigualasto Formation of San Juan, Argentina (Weishampel et al., 2004).

Biology:

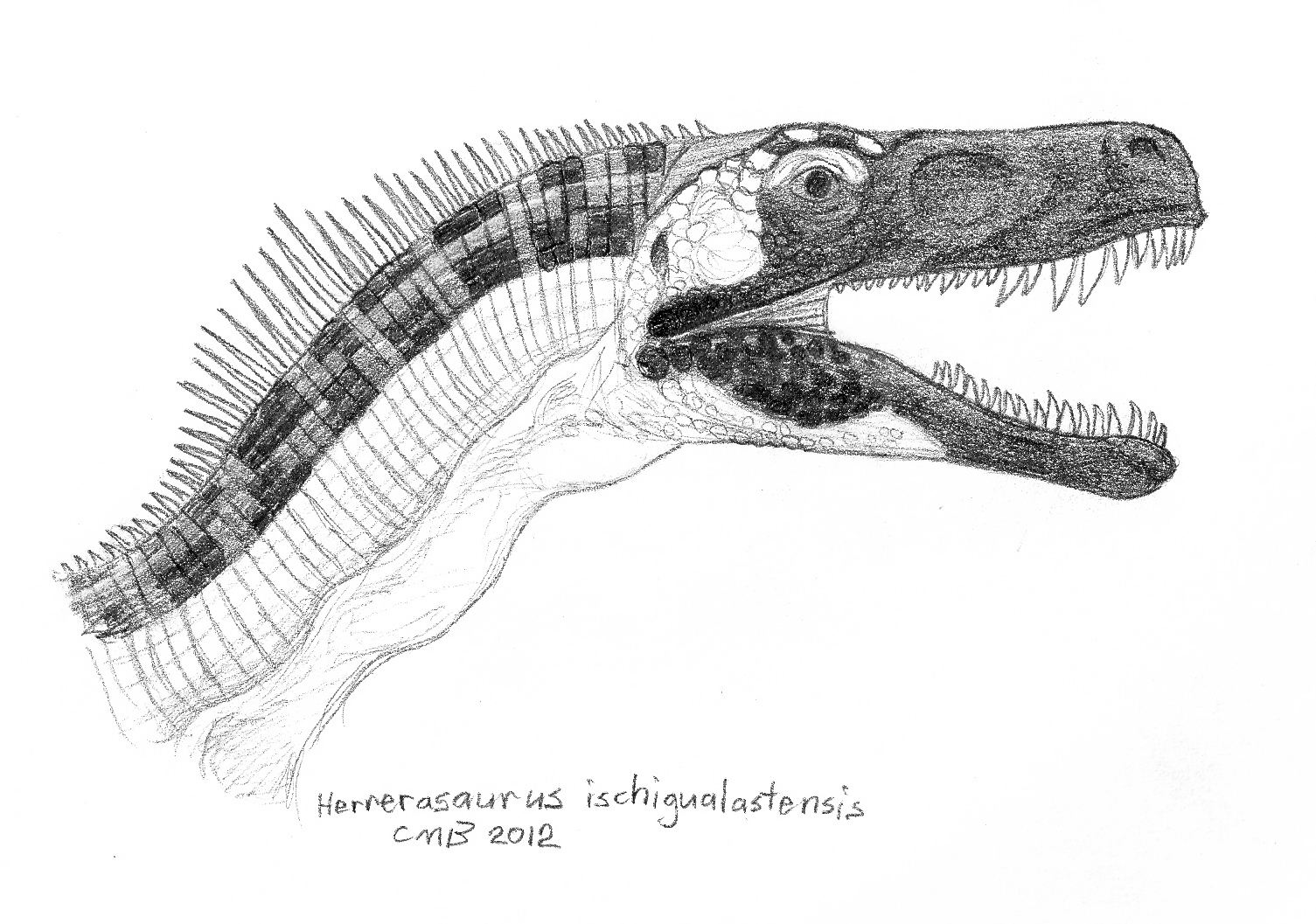

Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis is

the key species for all the Herrerasauridae. It is far more complete than other

species and can be considered the “typical” herrerasaur. Like others of the

family, H. ischigualastensis had four toes on its hind feet (though only three

of these bore weight), giving better traction and stability but less speed and

maneuverability compared to other theropods, but of these things it had no

need, because all its prey animals and the predators that might have hunted it

were slower still.

It

preyed on the smaller cynodonts and rhynchosaurs of its environment. To

dispatch these victims it probably used its large backward facing teeth. It

would make a lunge, perhaps with its five-fingered hand or perhaps with its

deep jaws. Once the teeth had been pushed into the flesh, there would be no

escape even for the most determined prey. It would have made short work of any

soft-bodied animal such as a cynodont by utilizing a hinge on the lower jaw

that allowed for a slicing action of the serrated teeth.

The

hands and jaws probably worked in coordination with each other to maneuver

prey. The arms were long and three of the fingers were long and clawed (the

other two were short and provided more of a grasping palm).

H. ischigualastensis was the most common predator in its environment

and had little to fear most of the time. However, it was not the top predator. Saurosuchus was a huge rauisuchian that

could have easily taken the life of a herrerasaur given the chance. Luckily,

rauisuchians are top heavy and move about on all fours so, as long as

Herrerasaurus kept its wits about it, it could out maneuver and out pace the

larger carnivore.

Herrerasaurus led a relatively quite life for a theropod. The

bones show no sign of stress so the animals would have done little active

movements that involved bashing, bruising, or other activities that might

stress the bones (Rothschild et al., 2001). This is supported by the scleral

rings (eye bones) which bear similarities to animals that are only active for

short periods throughout the day (Schmitz et Motani, 2011). However, some Herrerasaurus bones do have puncture

wounds that match the teeth of other Herrerasaurus,

so inter-species fights of a violent nature must have been fairly common. The

wounds had been infected, but healed successfully (Molnar, 2001). A herrerasaur

predator may have left some of these wounds, particularly those on the skull

(Sereno et Novas, 1993). Saurosuchus

is a likely culprit.

The

habitat in which H. Ischigualasto lived experienced both a wet and dry season

but it would have been at least fairly moist all year round. Ferns, horsetails,

and giant conifers would have been common, as in any Triassic-type habitat and

would have been thick across the forest floor. Signs of volcanic activity and

heavy rainfall indicate that these animals died during the global flood in a

situation probably involving volcanic activity.

Selected

Organisms:

Aetosauroides

schagliai

An

aetosaur of fairly plain features, having short legs that hold its body close

to the ground and no spines on the margins of its dorsal plates. It was about 3

meters (10 feet) long. It was a likely candidate for a Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis menu though, being so heavily

armored, it would not have been the easiest option.

Exaeretodon

frenguellii

An

herbivorous cynodont about 1.8 meters (5.9 feet) long, having large

incisor-like teeth at the front of its jaws. It was one of the largest

traversodonts and a likely food source for Herrerasaurus

ischigualastensis.

Hyperodapedon

sanjuanensis

A

strange, squat reptile with a beak and broad, flat head, it was only 1.3 meters

(4.3 feet) long. It was chunky and heavily built. Though it might have used its

narrow, sharp beak protruding form its upper jaw as a defensive mechanism, it

was also a very likely food source for Herrerasaurus

ischigualastensis, along with Exaeretodon

frenguellii.

Ischigualastia jenseni

A

large dicynodont which grew close to 4 meters (13.2 feet) in length and weighed

more about 2.5 tonnes. It was the largest animal in the Ischigualasto

Formation. It sported a frill-like structure around the back of its head to

protect the neck and had a horny beak with downward protruding edges, almost

like tusks. Its overall bulk of body is reminiscent of a hippopotamus. It would

have been a difficult task for a Herrerasaurus

ischigualastensis to bring down, but so much meat was likely worth the

effort.

Saurosuchus

galilei

At

9 meters (30 feet) long, this was the top predator of the Ischigualasto and

likely provided a consistent source of trouble for Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis. It was a rauisuchian, with a large

skull and deep jaws filled with large, serrated and curving teeth. While it was

certainly capable of hunting and likely targeted the large dicynodonts (above)

it would not have been above steeling kills from a begrudging Herrerasaurus.

Eoraptor

lunensis

A

small dinosaur similar in proportion to Herrerasaurus

ischigualastensis, but judging from its teeth, it was more of a generalist

taking invertebrates and even plants. It would likely have fallen prey to Herrerasaurus, given an encounter.

Notes:

Synonymous with Ischisaurus cattoi

and Frenguellisaurus ischigualastensis.

References:

Nesbitt, Sterling J.,

Randall B. Irmis, et William G. Parker. March, 2007. “A Critical Re-evaluation of

the Late Triassic Dinosaur Taxa of North America”. Journal of Systematic Paleontology. Volume 5, Issue 2. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1017/S1477201907002040#.UcjA66XNvao

Molnar, R. E. 2001.

“Theropod Paleopathology: A Literature Study”. From Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Darren H. Tanke and Kenneth Carpenter

(editors). Indiana University Press, Indiana. Pages 337-363.

Olsen, Paul E. and Donald

Baird. 1986. “The Ichnogenus Atreipus and its Significance for Triassic

Biostratigraphy”. From The Beginning of

the Age of Dinosaurs: Faunal Change Across the Triassic-Jurassic Boundary.

K. Padian (editor). Cambridge University Press, New York. Pg 61-87. http://www.ldeo.columbia.edu/~polsen/nbcp/olsen_baird_86.pdf

Paul, Gregory S. 1988. Predatory Dinosaurs of the World: A Complete

Illustrated Guide. Simon and Schuster, New York.

Paul, Gregory S. 2010. The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs.

Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Rothschild, Bruce, Darren

H. Tank, and Tracy L. Ford. 2001. “Theropod Stress Fractures and Tendon

Avulsions as a Clue to Activity”. From Mesozoic

Vertebrate Life. Darren H. Tanke and Kenneth Carpenter (editors). Indiana

University Press, Indiana. Pages 331-336.

Safran, J. et E. C.

Rainforth. 2004. “Distinguishing the Tridactyl Dinosaurian Ichnogenus Atreipus

and Grallator: Where are the Latest Triassic Ornithischia in the Newark

Supergroup?”. Abstracts with Programs.

Geological Society of America. 36(2): 96. https://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2004NE/finalprogram/abstract_70257.htm

Schmitz, Lars and Ryosuke

Motani. 2011. “Nocturnality in Dinosaurs Inferred from Scleral Ring and Orbit

Morphology”. Science. Volume 332,

Number 6030, pages 705-708. http://www.sciencemag.org/content/332/6030/705

Sereno, Paul C. and

Fernando E. Novas. 1993. “The Skull and Neck of the Basal Theropod Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Volume 13, Number 4, pages 451-476. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02724634.1994.10011525#.UdZzQqVuDao

Weishampel, David B., Peter

Dodson, et Halszka Osmolska (editors). 2004. The Dinosauria. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Hey Caleb, Great information. My question is: In paragraph 2 you say that the Herrerasaurus' had backwards facing serrated teeth and that any prey wouldn't be able to get away because of its hinged jaw. Then in paragraph 5 you say that two of those creatures would fight and that there are fossil finds that show wounds that have healed that would have been made by the teeth. So is this a contradiction or was there exaggerated liberties? I love you xo Mom

ReplyDeleteOuch. Ok, ok. Perhaps some exaggeration, but no contradiction. Prey animals would have some chance of escape, but most of these weren't as powerful and solidly built as a Herrerasaurus. For example when a fox catches a mouse, the mouse has practically lost its chance for escape once within the fox's jaws. However, if a fox gets in a fight with another fox (as may happen, especially in the breeding season) then, though there is a lot of biting, neither have to worry about "no escape." Sorry about the lack of clarity. In my defence, I wrote the article in one brief sitting and I probably have to do some editing.

Delete